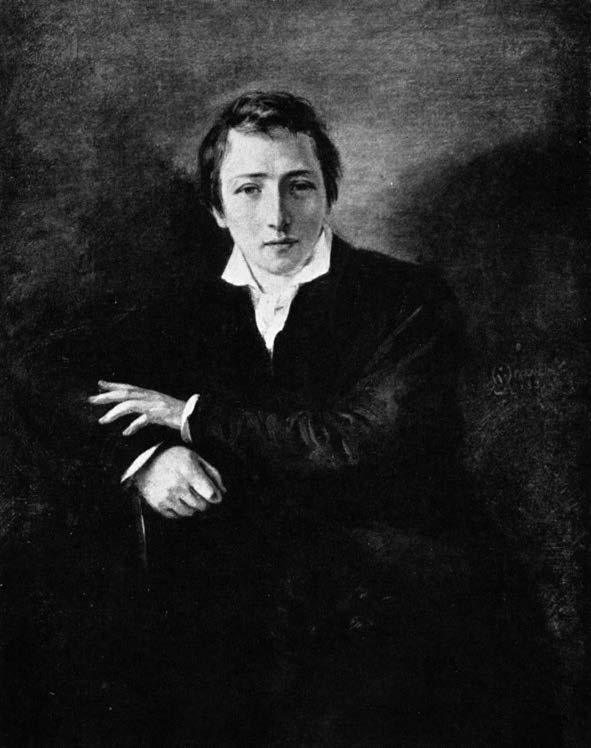

HEINRICH HEINE: GERMANY: A WINTER'S TALE.

Bilingual Edition in English and German. Translated by Jacob Rabinowitz.

Bilingual Edition in English and German. Translated by Jacob Rabinowitz.

In 1835, the German principalities and cities banned the works of German-Jewish poet Heinrich Heine. The censors banned not only the works Heine had already published, but also prohibited, in advance, any work the writer might produce in the future. When Heine sneaked across the border from his Paris exile in 1843, the result was the poem-cycle Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen (Germany: A Winter’s Tale). The Hamburg publisher Julius Campe published this book, and kept all of Heine’s work available “under the counter,” so that the banned poet was read even more widely than ever. Heine’s satires against German arrogance and militarism would continue in the 1840s, when the poet and Karl Marx worked together on the revolutionary newspaper Vorwärts. Heine’s books would be banned again by the Nazis, who made a point of burning his books, and erasing his name from published song lyrics. Even the most famous of all German Lieder, “The Lorelei,” was now said to have lyrics by “Author Unknown.”

Jacob Rabinowitz’s adaptation of the 27-poem cycle renders Heine’s verses into rapid-fire lines, almost as though Lenny Bruce were channeling his 19th century forebear. And instead of peppering the text with explanatory footnotes on the context of German culture and history in the poems, Rabinowitz incorporates helpful elucidations into the flow of the poems. For those who want to read the original German for themselves, this edition includes the complete 1844 German text on facing pages. With a Foreword by Brett Rutherford.

The 227th publication of The Poet's Press/Yogh & Thorn Books. ISBN 0-922558-86-8. 6 x 9 inches, 220 pages. $16.95. CLICK HERE to order paperback from Amazon.

To order the paperback from The Poet's Press:Order Paperback from Poet's Press

Hardcover edition published December 2021. ISBN 9798784067623. $21.95. CLICK HERE to order the hardcover edition from Amazon.

To order the hardcover from The Poet's Press:

Order Hardcover from Poet's Press

To purchase and download the PDF ebook for $3.00:

FROM THE FOREWORD BY BRETT RUTHERFORD

Few English-speaking readers are familiar with the poetry of Heinrich Heine. A student of “World Literature” will find four poems in the corresponding Norton college anthology series. Others know Heine as the brilliant poet whose words are the basis of some of the finest Lieder ever composed, by Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and many other composers. Several are masterpieces with a supernatural theme, such as “The Lorelei,” set by Silcher and Liszt, and “The Doppelgänger (The Double)” one of Schubert’s last songs. Since the preponderance of these settings are love songs and mood pieces, Heine’s admirers via music may not know of the firebrand Heine or the self-mocking satirist who created Germany: A Winter’s Tale.

Heine spanned three worlds: first, the German-Jewish culture of his boyhood in Hamburg; second, the giddy pan-German synthesis he absorbed at university spanning Greek myth, Lutheran theology, and philosophy through Hegel; and third, the liberal, anticlerical, revolutionary world of Paris, the city of his exile. Meno Spann, a perceptive intellectual biographer of Heine, sees the poet’s mind as a battleground of mythologies: the Age of Reason, the French Revolution, rival flavors of Judaism, Christianity, Greek myth, and the pagan nature-worship of the German forests, rivers and mountains. Through much of his life Heinrich Heine was the poet of Zerrissenheit (the state of being torn to pieces). ...

In 1843, Heine made the journey home to Hamburg, the basis for his Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen. His longing to see his homeland had become almost unbearable, and he feared that he would not get to see his mother again, as she was in her seventies (ironically, probably in better health than he was despite her feebleness). He had to bribe his way past the border guards. His reunion with his patron uncle Solomon was a happy one, and he had good meetings with his publisher Campe. But, torn as ever by Zerrissenheit, Heine nearly convinced himself that his wife had taken lovers in his absence, even though he had tucked her away in a convent school for safe-keeping. He champed at the bit to return home to Paris. His visit scarcely lasted two months and he was home before Christmas. By the middle of February, 1844, he had completed 20 of the 27 poems of Deutschland.

Heine and Mathilde visited Hamburg and his family again, later in 1844, but this would be the last time he would see his mother, or his native Germany. Years of horrific bad health followed, as the poet’s body and nervous system were wracked by syphilis. He would last longer than any of his doctors ever expected. In 1845, his father’s executor discontinued the poet’s family allowance, and in 1848, his French pension was withdrawn. From 1848 through his death in 1856, Heine was paralyzed, bedridden, an invalid in near-total darkness. He was buried at Montmartre in Paris. ...

Heine: Reception and Readership

The actual reception of Heine in his native Germany, then, is more than a history of successive proscriptions. His books were read, despite the bans, and Heine had defenders against the anti-Semites of his time. Since book-banning was not put in place simultaneously in all locales, reviews could be published in one city where a books was not yet banned, and the review would be read elsewhere, prompting demand for the forbidden book. A book talked about, even if banned, remained in the discourse, a tantalizing fruit to be plucked. (Retroactive “nonpersonhood” had not yet been invented.)

Heine had, and has, multiple readerships as well. It might be said that ordinary Germans read Heine for his love poems; that assimilated German Jews read Heine with a special grasp of his ironies; and that revolutionaries had their own Heine whose youthful sentimentality had been only a prelude to mature political awareness. The backward-glancing critical reader of today can take in all of this, a mix of irony and Zerrissenheit. As the present book attests, Heine’s poetry is read everywhere. The French knew his work intimately from the French editions he created with collaborators. The audience for art-songs knows Heine’s lyrics for Schubert, Schumann and other composers. Forty Heine poems are translated for inclusion in Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s compendium of Lieder lyrics. And no anthology of German literature in translation would be complete without some selections from Heine. Yet Heine seems not to have attracted many poet-translators and there is no current facing-pages complete edition of Heine in German and English.

The Text for This Edition

Jacob Rabinowitz’s English version of Germany: A Winter’s Tale appeared in 2009 in a book from Invisible Books, but without the original German text. This text, revised and corrected by the translator, is now repaginated for facing-pages German and English presentation. The German text presented here was prepared, using the Project Gutenberg public domain text of the poem cycle, formatted in 2004 by Gunther Olesch and Andrew Sly, as a starting point. We compared this text line-by-line with the 1971 Carl Hanser Verlag edition, edited by Klaus Briegleb. We corrected a handful of errors in the Project Gutenberg text, mostly words which had been run together. The Hanser Verlag text, however, had itself been subjected to modernization of spelling and capitalization, so we turned to the original 1844 black-letter German edition, and Campe’s revised edition of 1857, for further editing. We restored Heine’s original use of quotation marks, capitalization and some of his spelling. So what is presented here is a hybrid: it is the standard 1844 version of Deutschland, with some of the quaintness of older spellings and style restored.

Jacob Rabinowitz has rendered Heine with a special voice. He captures Heine’s manic intensity, whether it be his address to the wolves of the German forest, or his rhapsodic nostalgia for German home cooking. The meeting with the shade of Frederick Barbarossa, and that king’s reaction to learning about the Guillotine, is political satire worthy of Voltaire. Deeper still, Rabinowitz captures the nervous, Jewish outsiderness to both the French and German cultures that attracted and repelled Heine in his quest for an intellectual homeland: he belongs to neither and can only use the virtues of one as a barb against the other. The result is a tone of sarcasm and self-mockery. Heine can render this sarcasm in delicate light verse, each stanza a barbed bumblebee: Rabinowitz puts on the guise of the stand-up comic, and these versions of Heine could almost be a script for a Lenny Bruce.

Version 24.3 Updated January 27, 2026.

History of the Press

Book Listings

Anthologies

- Opus 300

- Wake Not the Dead!

- On the Verge

- Group 74

- Meta-Land

- Beyond the Rift

- Tales of Terror (3 vols)

- Tales of Wonder (2 vols)

- Whispering Worlds

Joel Allegretti

Leonid Andreyev

Mikhail Artsybashev

Jody Azzouni

Moira Bailis

Callimachus

Robert Carothers

Samuel Croxall

Richard Davidson

Claudia Dikinis

Arthur Erbe

Erckmann-Chatrian

Michael Frachioni

Emilie Glen

Emily Greco

Annette Hayn

Heinrich Heine

Barbara A. Holland

- The Holland Reader

- After Hours in Bohemia

- Selected Poems 1

- Selected Poems 2

- Shipping on the Styx

- Out of Avernus

- The Beckoning Eye

- The Secret Agent

- Medusa

- Crises of Rejuvenation

- Autumn Numbers

- Holland Collected Poems

- In the Shadows

Victor Hugo

Thomas D. Jones

Michael Katz

Li Yu

Richard Lyman

Meleager

D.H. Melhem

David Messineo

Th. Metzger

J Rutherford Moss

Denise La Neve

Ovid

John Burnett Payne

Edgar Allan Poe

Suzanne Post

Shirley Powell

Burt Rashbaum

Ernst Raupach

Susanna Rich

Brett Rutherford

- New and Recent Poems

- Goodman's Croft

- From Hecla

- Big House, Rent Cheap

- Island of the Dead

- Story of Niobe

- The Inhuman Wave

- Fatal Birds

- Pumpkined Heart

- Doll Without A Face

- Crackers At Midnight

- Anniversarius

- Gods As They Are, 2nd ed.

- Prometheus on Fifth Ave

- Things Seen in Graveyards

- Prometheus Chained

- Dr Jones & Other Terrors

- Trilobite Love Song

- Expectation of Presences

- Whippoorwill Road

- Poems from Providence

- Twilight of the Dictators

- Night Gaunts

- Wake Not the Dead!

- Pity the Dragon

- It Has Found You

- Autumn Symphony

- By Night and Lamp

- September Sarabande

- Midnight Benefit St.

Boria Sax

Charles Sorley

Vincent Spina

Ludwig Tieck

Pieter Vanderbeck

Jack Veasey

Don Washburn

Jonathan Aryeh Wayne

Jacqueline de Weever

Phillis Wheatley

Sarah Helen Whitman

Section Links

Featured Poets

- Joel Allegretti

- Jody Azzouni

- Boruk Glasgow

- Emilie Glen

- Annette Hayn

- Barbara A. Holland

- Donald Lev

- D.H. Melhem

- Shirley Powell

- Brett Rutherford

- Jack Veasey

- Don Washburn

- Poe & Mrs. Whitman