LAST FLOWERS: THE ROMANCE AND POETRY

OF EDGAR ALLAN POE AND SARAH HELEN WHITMAN

Preface:

Raven and Dove

Contents

READ THE POEMS (LINK)

POE & MRS. WHITMAN: RAVEN AND DOVE

ANYONE who has ever thrilled to the euphony and cadences of Poe — either as a youngster, or, like myself, as a superannuated youth — has no doubt wondered: were there others like Poe? Was he unique in his cosmic scope, his brooding and fevered flight into worlds of fantasy, his nocturnal haunting of tombs and cypress groves? There was at least one other — the Providence poet Sarah Helen Whitman. This brilliant and eccentric woman was Poe’s spiritual equal, and their calamitous romance was one of the great misfortunes in the history of literature. Their poetry, published here together for the first time, demonstrates not only the depth of her intellect, but the remarkable ways in which their works complement one another.

In this book you will encounter a poet whose mind encompasses the entire range of 19th Century Romanticism, and whose poems, under the spell of Poe, walk side by side with his in the misty mid-regions of Weir.

Is she Poe’s literary equal? Alas, there is only one Poe. But as a companion and sequel to Poe, she has much to recommend her. If you love Poe, you will like or even love Sarah Helen Whitman. If your heart is open to the passion, sorrow and tragedy of this “almost” liaison of two brilliant intellects, you will find this colloquy of their poems a wrenching one.

EDGAR Allan Poe visited Providence, Rhode Island six times, beginning in September 1848, to win the affections and promise of marriage of Sarah Helen Whitman. He spent as many as 28 days in the College Hill neighborhood, an area still haunted today by memories of his presence. Grief-stricken after the death of his young wife Virginia by consumption, and alienated from the New York literati, Poe conducted an intense but doomed courtship of Rhode Island’s most prominent female poet. She would live until 1878, publishing her poetry and fostering generations of younger writers and artists; Poe, hurtling to his ruin, had less than ten months to live when he left Providence for the last time in 1848.

To make better sense of a strange romance already told many times in the present tense, we turn first to the historical record to determine what we can learn about the family to which Poe wished to join his destiny.

The Powers were in Rhode Island almost from the beginning. There would be five Nicholas Powers in the family, the last of them Sarah Helen Whitman’s father.

The first Nicholas Power received a home lot in Providence in 1640. He was in trouble briefly with the British authorities for trying to purchase Indian lands in Warwick (RI) — expressly forbidden in the treaties with the local tribes — and was “dismissed with an admonition.”

Nicholas died in 1657, leaving his widow, Jane Power, a daughter, Hope, and the next Nicholas Power. This Nicholas died in the catastrophic King Phillip’s War in 1675. He is not found in lists of combatants I examined, so he may have been killed in an Indian raid.

His son, Captain Nicholas Power, was born in 1673. This Nicholas’s second wife was Mercy Tillinghast, daughter of the ominously-named Rev. Pardon Tillinghast. Captain Power died in 1734. (A divergent record indicates Anne Tillinghast as his wife and places his death at 1744.) This Captain Power was a merchant and distiller. He sold his estate and distillery in Dutch Guiana to Captain John Brown in 1743.

In the next generation, we have another Captain Nicholas Power, who was a merchant and rope-maker. He was married to Rebecca Corey, and died January 6, 1808. The records indicate he freed a Negro slave in 1781 (we hope it was the only such soul he “possessed.”)

The Nicholas who figures in our story is the fifth, known as Nicholas Power, Jr., born September 15, 1771. He married Anna Marsh, daughter of Daniel and Susanna (Wilkinson) Marsh on August 28, 1798 in Newport. Genealogical records indicate he was a merchant, going by the title of Major for some part of his life.

His mercantile life seemed to be land-locked: he formed a partnership as “Blodgett and Power” and opened a store near Providence’s Baptist Meeting House. The goods sold there began with fabrics, linens, threads (English, Indian and Scottish), then dry goods, hardware and groceries. From 1808 to 1810 the store ran auctions of goods. Then, in 1812, the partnership terminated. The war with the British almost certainly interrupted their trade.

The genealogy records at The Providence Historical Society note, “He was absent from Providence much in later years.” Helen Whitman’s biographer Caroline Ticknor tells us that Nicholas Power took to sea to build back his fortune, and was captured by the British during the War of 1812.

He was not released until 1815, at which time he did not return to Providence. He was not seen or heard from in Rhode Island until around 1832 or 1833, when he made a sudden return to “make amends” and resume his family life. Indications are that his nineteen-year “widow” was aghast at his return and threw him out of the house. He took up residence in a Providence hotel, and, to the dismay of all, spent the years until his death on April 28, 1844, in conspicuous dissolution. In 1842, he got around to placing a marker on his mother’s grave with an inscription lamenting the effect of his long absence on his parent’s well-being. (Rebecca Corey Power had died in 1825, and it is likely that she never knew what became of her son).

This family history, with the particular details of paternal abandonment and irresponsibility, is important to our story.

Nicholas and Anna’s first child, Rebecca, was born in 1800. Sarah Helen Power, our and Poe’s “Helen,” was the second daughter, born in Providence on January 19, 1803. The house where she was born was that of her grandfather, Captain Nicholas Power, at the corner of South Main and Transit Streets. They lived in this house until her grandfather’s death in 1808.

As the younger Nicholas Power’s fortunes ebbed and flowed, the young family moved to a succession of houses and lodgings: a house at the corner of Snow and Westminster (now a parking lot in a depressed corner of downtown Providence); “the Grinnell House,” and “the Angell Tavern,” which had a garden leading to the water.

Sarah Helen’s younger sister, Susan Anna, was born in 1813. Hers was a dark-shadowed life: daughter of a merchant euphemistically “lost at sea,” she would mature into a willful manic-depressive, the classic mad relative without whom no New England house seemed complete.

After 1816, Mrs. Power purchased a house at 76 Benefit Street (now No. 88) as a residence for herself and her daughters. This was a splendid avenue perched on the hillside overlooking Providence’s busy waterfront. It would be their home for more than four decades. The city’s “College Hill” boasted fine mansions, classic churches and a small colonial burial ground just a few minutes’ walk from their door (St. John’s churchyard). The family was well able to live on the stocks and mortgages Mrs. Power had inherited from her mother, funds happily untouched by the impecunious Major Power.

Although Benefit Street was then fashionable, the street’s origins would have pleased Edgar Poe’s morbid tastes. The original settlers of Providence owned long, parallel strips of land starting at the river and running up over College Hill. Until 1710 or so, most families buried their dead on the hillside, and a lane that threaded among these family burial plots was what ultimately became Benefit Street. For many decades it remained a twisted street, bending round grave plots and old houses whose owners had not yet yielded the right-of-way, until it finally became the straight avenue we know today. For some years, the street terminated with a gate, to ward off the denizens of the sinister North End.

To the north of Benefit Street, the 22-acre North Burial Ground was created in 1700, but the town’s families did not begin burying the respectable dead there until 1711. With the creation of Benefit Street, the city fathers persuaded families to exhume and relocate their moldering ancestors to the North Burial Ground. (A few thrifty old families, it may be guessed, merely moved the gravestones.) A number of gloomy and derelict churchyards were also relocated there gradually, but St. John’s churchyard remained, its wall abutting the Powers’ rose garden.

Although a proper Providence upbringing in those days was probably rather stifling to the intellect, Helen had a few escapes during her younger years: she visited relatives on Long Island, New York and briefly attended a Quaker school. Despite the Puritanical suspicions and prohibitions of her relatives, she developed an early passion for poetry. She mastered Latin and would later be sufficiently adept in languages to read and translate both German and French.

In 1821, Sarah Helen’s older sister Rebecca married William E. Staples. Two children were born to them in rapid succession. There is a Judge William Staples home just up the block from the Power house on Benefit Street, and this may be where the couple lived.

Despite her mother’s deep-set mistrust of the male gender, Sarah Helen, too, was wooed and won away from the Benefit Street home. In 1824, during her twenty-first year, she was engaged to attorney John Winslow Whitman. Urged to assume the proper responsibilities of womanhood, Helen was pressured to put aside her literary ambitions. As her biographer Caroline Ticknor tells it, “Mrs. Whitman’s taste for poetry was frowned upon by certain relatives...[She received] reproving letters, expressing the hope that she ‘did not read much poetry, as it was almost as pernicious as novel-reading.’”

Mr. Whitman seemed a good match. He was not one of those lawyers whom Shakespeare would have us kill. The third son of Massachusetts Judge Kilborne Whitman, he graduated from Brown University in 1818. He started a law practice in Boston, and practiced later in Barnstable.

During their long engagement, in 1825, Sarah Helen’s grandmother, Rebecca Corey Power, died.

Sorrow struck again that year when Sarah Helen’s older sister Rebecca died on September 14th. She had been married only four years, and then her two children, according to the Power family records, “died young.” Was her death childbirth-related, or did a contagion such as tuberculosis (”the galloping consumption”) sweep through the Staples home, taking the young mother and then the children? This tragedy must have made a deep impression on the poetical Sarah Helen, who would have followed four coffins to the North Burial Ground in swift succession.

Sarah Helen’s respectably-delayed marriage took place in 1828, with a Long Island wedding held on July 10th at the home of Sarah Helen’s uncle, Cornelius Bogert. A four-year engagement may seem excessive by today’s standards, but we can assume that Mr. Whitman also needed time to establish his law practice and set up a suitable home.

John Whitman turned out to have a creative side, too. It is interesting to note that Helen’s biographers, and most of Poe’s, seem to know Sarah Helen’s husband only by his profession. I was startled to discover, during an Internet search, that John Winslow Whitman had another persona altogether: he was co-editor of The Boston Spectator and Ladies’ Album. This journal published some of Sarah Helen’s poems, under the name “Helen.” Through her husband’s Boston affiliations, she met and came to know the whole circle of Transcendentalists, and started writing and publishing essays on Goethe, Shelley and Emerson. Articles and poems in other magazines soon followed. Mrs. Whitman was clearly not going to vanish into the draperies, and she was fortunate to have a literary ally in her husband.

A few years later, a new kind of turmoil roiled the family. Sometime between 1831 and 1832, Sarah Helen’s mother lost the right to wear her widow’s bonnet, with the sudden reappearance of the wandering Nicholas Power. Did the Major return in a remorseful state, wanting to make amends and restore his family’s fortune? Or was he ruined again, returning to old haunts to nibble away at his wife’s property? Another legend has it that he had a second wife and family in the Carolinas, and had now abandoned them, too.

Sarah Helen, who had cherished a somewhat heroic image of her father, was crushed — and one can only imagine the effect of all this on the younger sister.

Like her father, Sarah Helen’s husband was not destined for commercial success. Money vanished into failed inventions, and several business ventures went belly-up. Mr. Whitman even appears to have gone to jail for a few months in a legal upset involving a bad loan — not a happy career turn for a young attorney.

Worse yet, John Whitman also turned out to have a frail constitution. He caught colds frequently, and one of them, contracted in 1833, lingered and worsened into a total collapse and sudden death.

In 1833, then, Sarah Helen Whitman found herself a widow after only five years of marriage. She donned the official “widow’s bonnet” and moved back in with her mother and younger sister on Benefit Street.

Although she would continue to be the dutiful daughter, Sarah Helen was now a published literary figure in her own right, confident in her worth and powers, and acquainted with many of the best minds of New England.

Meantime, Nicholas Power, rebuffed from the attractive red house on Benefit Street, had set up lodgings in a Providence hotel and began his new, disreputable existence, pursuing ladies of the theater. The prejudice against theater people was so strong in America at this time that actors were routinely forbidden the use of churches for weddings and funerals. So it is possible that the contemporary reference to “actresses” was a euphemism implying all kinds of women of the lower sort.

At this time, the Power-Whitman household probably assumed its frozen triangle of control, dependence and artistic defiance. One thinks of immobile Chekhov characters, locked in their parlor.

Mrs. Anna Power held the purse strings. She would make certain that no man ever got near the modest fortune that had come their way through the Marsh family.

Susan Anna careened between manic highs and long periods of sullen silence. One episode reportedly led her to a sanitarium stay, for “mania,” but Mrs. Power evidently preferred the cheaper long-term solution of keeping her daughter at home, under constant supervision.

Mrs. Power probably established some stern rules about the extent to which Susan’s mood swings would be humored — after her death, Sarah Helen seemed to surrender control to her reclusive “patient.” In those latter years, during Susan’s depressive periods, the house would be darkened and visitors turned away. Her need for silence, darkness and solitude were pampered, and if visitors were by some necessity admitted, Susan would hide in a closet. In her manic phases, Susan Anna collaborated on some well-wrought fairy-tale poems with Sarah Helen, and amused visitors with impromptu verses about the errant Nicholas Power. (I have written a little blank-verse mystery poem speculating about the nature of Susan Anna Power’s madness. To read it, CLICK HERE.)

Sarah Helen’s outward personality had probably bloomed during her Boston days, and although she would accept the burden of living with her embittered mother, and helping to care for her sister, her mind, and her writing, were unfettered. She was with the gods — Goethe, Schiller, Shelley, Byron, Emerson. She studied occult lore and learned about mesmerism and spiritualism, as interest in these phenomena swept across the New England states. And when universal male suffrage, women’s suffrage, and the abolition of slavery became New England’s predominant issues, Sarah Helen was there. Séances, poetry and political activism, all hand-in-glove.

An avid reader, she frequented the wonderful Providence Athenaeum, a membership lending library which opened its new Greek-revival temple only a few blocks away on Benefit Street in 1838. According to Jane Lancaster, the Athenaeum’s historian, there is no indication Helen was ever a member or “share holder” at the Athenaeum. I suspect her mother would not part with the cost of membership, so Sarah Helen borrowed books on the card of one of her Tillinghast relatives. She became a local celebrity, and parties and salons at her home drew not only the locals, but visiting celebrities such as Emerson. John Hay, a young poet later famed as Abraham Lincoln’s secretary, was a devotee at the Power salon.

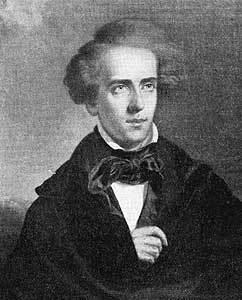

Sometime in 1838, Sarah Helen posed for a portrait, an oil painting by Giovanni Thompson that depicts her in a widow’s cap with pink strings. This portrait of the 35-year-old poet occupies a place of honor in the Art Room of the Providence Athenaeum.

THE OTHER PROVIDENCE POET: WILLIAM J. PABODIE

In 1838, if not sooner, Sarah Helen would have made the acquaintance of William Jewett Pabodie, a Providence student who had been elected class poet by that year’s graduating class of Brown University. He is of special interest since he plays a much-misunderstood role in the Poe-Helen romance.

Pabodie was making a name locally as a poet. He wrote a poem for the dedication of the Providence Athenaeum. He translated Goethe’s “The Elf King” from the German. He declaimed his long poem, “Calidore,” at the Brown graduation ceremony. Few listeners made it to the end of this forlorn Romantic poem of a drowned bride and a bereaved groom’s suicide. A poem whose ending is littered with corpses is not an auspicious commencement piece, but it was Pabodie’s magnum opus and he probably could not resist thrusting it upon the public. (To read Pabodie's Calidore as it appeared in print in 1839, CLICK HERE.

Pabodie, doubtless with parental funding, immediately published Calidore as a book. He was parodied and mocked locally (one newspaper dubbed him “Mistress Nabodie.”)

He tried throughout 1840 to get Providence’s best families to subscribe to the founding of a literary magazine, which he intended to call The Argosy: A Critical Journal of Literature and Art. Two other prospective journals had been spurned by Providence in the preceding two years. When the first issue of the Transcendentalist journal The Dial appeared, Pabodie published an unfavorable sour-grapes review, saying, “the poetry scattered throughout the volume is generally of no high character.”

William Pabodie would remain on the Providence literary scene for decades, writing and publishing poetry. He did little else. Although he read at law and was admitted to the bar in 1838, he never took up the practice, and was essentially a gentleman of leisure.

He also took up morphine and laudanum, and the pursuit of the poppy would go on till the end of his days. In his last decade he wrote no poetry at all. A look at his poetry, latter life and death leaves strong evidence that he was gay (then the most secret of secret societies). If you doubt this, go find his long prose poem with the refrain “Oh, sailor boy!” Or read the account of his lurid 1870 suicide by ingesting Prussic Acid. Printed ridicule of Pabodie cast allusions on his sexual orientation if not gender, suggesting that he was best suited to take up sewing.

Further clues about Mr. Pabodie come from Helen herself, who seemed to distance herself from him after the Poe affair. She referred to Pabodie as “Poe’s friend” rather than “my friend.” Writing to Poe biographer John H. Ingram in 1874, she described Pabodie thus:

He studied law, had a law office, & was a justice of the peace for several years, but he had an utter aversion to business, &, not being dependent on the profession for a support, soon abandoned it. He was a fine belles lettres critic, & has written a few very fine poems. Some of his patriotic & occasional odes have been quoted as among the noblest in our American literature. He was rather superfine in dress and manner, witty & sarcastic in conversation, very sensitive to the world’s praise & blame, & very indolent.

LITERARY NEW ENGLAND

IN THE 1840s

DURING these years, Sarah Helen maintained her place in a literary America that was exploding with new philosophical ideas. Despite the pious underpinnings of New England society, the 1840s were a decade of intellectual turmoil: end-of- the-world prophecies, new native religions, Brook Farm, the antislavery movement, spiritualism, and the restless intellectual odyssey of Emerson and the Transcendentalists. Science was advancing in leaps and bounds, and poets and essayists all felt that they had to take it all in and make sense of it.

Their problem was that they carried all the baggage of Platonic thought in a world that was becoming mechanistic and Aristotelian. It may seem strange to us that the same persons who read natural science and astronomy tomes also troubled themselves about souls, ghosts and Divinity. This is the complex world in which they lived. We can laugh at Transcendental abolitionists talking at seances to ghosts of dead Indians, but we do not have to look far to see equally bizarre belief-complexes among the intellectual class today.

The 1840s also represented a watershed for literacy and the appreciation of culture in America. Boston really was the Athens of the United States, and the roster of American writers active in mid-century was staggering. The Lyceum movement brought thousands of young people to hear writers and artists lecture, and lending libraries insured that working class people could have access to books. The prices of books were also falling dramatically during that period because of the introduction of the rotary printing press. Americans were proving to the world that high culture was for everyone. For an overview of literary America during this period, one of the best sources is still the classic book, The Flowering of New England: 1815-1865, by Van Wyck Brooks (E.P. Dutton, 1936).

During the early 1840s, Edgar Allan Poe had made his mark with stories, criticism, literary hoaxes and poems. His career was followed with interest, if not always approval, by his fellow critics. He had pretty much thrown the gauntlet against the New England literati in favor of the writers of New York and points south, and he had even accused Longfellow of plagiarism.

At the end of June 1845, Poe was lured to Providence. A drunken Poe told his friend Thomas Holly Chivers on a Manhattan street, “I am in the damndest amour!” and says of the poet Mrs. Fannie Osgood, “I have just received a letter from her, in which she requests me to come on there this afternoon on the four o’clock boat.” Poe, penniless, borrowed money for the journey, and was in Providence on or around July 1.

Fannie Osgood doubtless wanted to show off Poe on her rounds of social and literary visits. Possibly embarrassed by his empty pockets, his forlorn attire, and the uncertainty of his night’s lodgings, Poe refused to be taken to Sarah Helen’s house. (He may also have dreaded the Boston luminaries he might find there.) Instead, he wandered the streets of College Hill into the late hours.

Walking alone in the moonlight on Benefit Street, Poe recognized Helen’s house from Mrs. Osgood’s description, and caught a brief glimpse of the poet in her rose garden before she vanished into the rear of the house. It was a vision he could not forget. It is still possible to stand at the same corner today, peering into the same rose garden, hoping for a ghostly fluttering of Attic scarves and shawls.

Sarah Helen, for her part, was well aware of Poe in 1845. His magazine stories horrified and appalled her, yet she went back to them again and again. Poe’s avowed belief in the power of souls to go back and forth from Death attracted her, and his poetry overwhelmed her. She wished to know him, yet knew from gossip from her friends, that he was scandal-prone, impoverished, and married to a young cousin whose declining health was his all-consuming concern. (Well, not all-consuming — here he was on the arm of the controversial New York poetess, scandalously separated from her painter husband.)

Meantime, Sarah Helen had settled into the eccentric style of dress and speech that Caroline Ticknor described thus: “deep-set eyes that gazed over and beyond, but never at you ...her movements were very rapid, and she seemed to flutter like a bird. … Her spell was on you from the moment she appeared… when she spoke, her empire was assured. She was wise, she was witty … her quick, generous sympathy, her sweet, unworldly nature, her ready recognition of whatever feeble talent, or inferior worth another person possessed. … throughout her life she had a succession of adorers.” Of her style, Ticknor tells us further, “[S]he loved silken draperies, lace scarves and floating veils … always shod in dainty slippers … [she] always carried a fan to shield her eyes from glare. Her rooms were always dimly lit.”

The latter-day figure of Isadora Duncan comes to mind in this description, not surprisingly. Sarah Helen identified with Athena, so it was only natural that she should don the goddess’ helmet for an occasional party. Poe biographers have made sport of Helen’s appearance, describing how friends trailed her on the street, retrieving for her the various scarves and parts of her costume that always seemed to be falling off. Helen’s pagan garb was pretty daring in a very conventional city.

Somewhere in these years, Sarah Helen also became convinced that she had a weak heart. By the time Poe came calling, she carried a tiny bottle of ether and a handkerchief with her at all times. Sniffing the ether was believed to ward off heart troubles; a more substantial dose guaranteed a convenient fainting swoon. Helen was able to fend off would-be husbands with this heart complaint, assuring them (and Poe as well) that while the exertions of the marriage bed might result in mutual ecstacy, for her this would also be certain death.

Helen had friendships that spanned Providence and New York. One of the New York poets known to Poe, Anne Lynch, was one of Helen’s correspondents. From her and others, Sarah Helen had learned all about the consumption death of Virginia Poe in 1847, Edgar’s own troubles, and his desperate poverty. She also made inquiries about whether Poe’s seeming expertise in mesmerism was based on fact, since she was studying the literature on hypnotism with great enthusiasm. (This is back in the days when mesmeric influence was done with magnets as well as the waving of hands.)

IT is beyond the scope of the present book to outline the well-known biography of Poe. Our narrative, however, requires a knowledge of what Poe was up to during 1845 to 1849, the years in which his story and Helen’s intertwine.

In 1845, Edgar Poe’s personal, financial and romantic calamities piled one upon another in New York. Poe gained control of The Broadway Journal and secured financing for it. By late July his backer was referring to Poe as “a drunken sot.” Poe’s book of Tales Grotesque and Arabesque, meantime, was being reviewed everywhere, and the fame of his poem, “The Raven,” flew throughout the states. In August, a visitor to the offices of The Broadway Journal found Poe “irascible, surly, and in his cups.” In the August issue of the Journal, Poe reviewed a poem by Lowell and accused him of plagiarizing Wordsworth, and inaccurately quoted Wordsworth to prove it. Lowell wrote to Poe’s partner that his editor lacked character, and got a commiserating letter back saying, “[Poe’s] presumption is beyond the liveliest imagination.” By the end of August, Poe was begging a $50 loan from Chivers to sustain the magazine.

On October 1, despite all these troubles, Poe sent the manuscript of The Raven and Other Poems off to the printer.

Poe managed to irritate the Boston literary world on October 16, when he was paid $50 to read a new poem as part of a Lyceum program. Unable to write anything new for the entire preceding month, Poe trekked to Boston and substituted “Al Aaraaf,” a juvenile work, re-titling it “The Messenger Star.” He did an encore reading of “The Raven.” Then he went home and boasted in The Broadway Journal of having given Boston old goods. Reviews in Boston suggested that most of the audience fled before the poem was over, and numerous letters to journal editors pilloried Poe over his behavior.

Poe’s tale, “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” was circulated at this time under several titles in newspapers and magazines, and caused a stir in New England, where it was taken by many to be a factual account. It describes a man whose soul was retained after death through the power of hypnotism. The final sequence, in which Valdemar’s body dissolves into a putrescent mass when the hypnotic spell is broken, should have made it clear that this was a horror story. Sarah Helen Whitman, a student of mesmerism, wrote to friends in New York, begging to know whether Poe’s story was true.

Sarah Helen would later write: “I can never forget the impressions I felt in reading a story of his for the first time … I experienced a sensation of such intense horror that I dared neither look at anything he had written nor even utter his name … By degrees this terror took the character of fascination — I devoured with a half-reluctant and fearful avidity every line that fell from his pen.”

In October, Poe, with borrowed money, bought total ownership of The Broadway Journal. He then continued to beg friends and fellow authors for $50 loans.

By November 19, Poe had turned financial management of the Journal over to publisher Thomas H. Lane, retaining editorial control. That same day, Wiley & Putnam issued The Raven and Other Poems. By the end of month, Poe was begging a distant relative in Georgetown for a $200 loan.

In mid-December, Thomas Lane shut down The Broadway Journal after Poe vanished during a drinking binge, leaving the last issue of the magazine unfinished.

Poe was a brilliant editor and a feared critic, but he was clearly no businessman. In mid-1846 he was forced to flee to cheaper lodgings, moving along with his ailing wife and Mrs. Clemm, his mother-in-law, to a cottage at Fordham, The Bronx, 13 miles from lower Manhattan. By year’s end, magazines and newspapers were describing the Poes as destitute and near starvation.

Poe’s wife Virginia died of consumption on January 30, 1847. Later in the year, Poe won $225 in a libel suit, enjoyed the charity of the few New York literary ladies whom he had not offended, and published sketches of the New York literati in Godey’s Lady’s Book. He continued to live at Fordham with Mrs. Clemm (“Muddie”), Virginia’s mother.

By November 1847, Poe’s friends extracted the manuscript of “Ulalume” and persuaded a publisher to pay for it, so that the money might be used — to buy the poet a pair of shoes. All the parties to the transaction pitied Poe, and all agreed they had no idea what the poem meant, despite its almost overwhelming beauty of language.

As 1848 began, Poe was busy writing his cosmological essay, Eureka, and drafting plans for his literary magazine, The Stylus. All he needed to launch his magazine, of course, was money.

THE YEAR 1848 — MEETINGS AND CALAMITIES

UNTIL very recently, most accounts of the Poe-Helen romance had essentially the same details, but often formed a vague chronology. “On one of Poe’s visits...” we often read. Thanks to the latest in Poe scholarship, I have been able to collate, from several sources, a real chronological account of the Poe-Helen affair, with most of the dates in place. Just as we can best understand the psychology of Helen by tracing her whole family history, we can best understand the sometimes lunatic turns of the romance of the two poets by putting things in order.

In the first edition of this book I discussed the affair in more general terms, content to let the reader do his or her own researches. Since then, my own fascination with the characters in this drama has deepened, and, having elaborated the Power family history in chronological order, let us plunge forward. (Thanks be to The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe compiled by Dwight Thomas and David K. Jackson, and to the clear-headed narrative of Kenneth Silverman in Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance.)

Although not all the events listed in the following pages may seem relevant, they all bear upon Poe’s and Helen’s state of mind during the year.

On January 1, 1848, The Home Journal reprinted Poe’s poem “Ulalume,” anonymously.

On February 3rd, Poe baffled a New York City lecture audience with his long, long talk on “The Universe,” his first public presentation of his prose-poem Eureka. During the rest of his days, Poe would recite from his epic description of the creation and destruction of universes on the slightest pretext. He was convinced that he had “guessed” the deepest secrets of science, and he would expound to anyone who would listen (including drunks in taverns.) Poe’s mammoth essay on astronomy and metaphysics has, as one of its final passages, the following:

No thinking being lives who, at some luminous point of his life of thought, has not felt himself lost amid the surges of futile efforts at understanding, or believing, that anything exists greater than his own soul. The utter impossibility of any one’s soul feeling itself inferior to another; the intense, overwhelming dissatisfaction and rebellion at the thought; — these, with the omniprevalent aspirations at perfection, are but the spiritual, coincident with the material, struggles towards the original Unity — are, to my mind at least, a species of proof far surpassing what Man terms demonstration, that no one soul is inferior to another — that nothing is, or can be, superior to any one soul — that each soul is, in part, its own God — its own Creator: — in a word, that God — the material and spiritual God — now exists solely in the diffused Matter and Spirit of the Universe; and that the regathering of this diffused Matter and Spirit will be but the re-constitution of the purely Spiritual and Individual God.

This woolly pantheism is an odd song for a writer who mocked Emerson and the New England thinkers. It is also patently blasphemous against the views of everyday Christians. Poe’s book may in part be a response to a popular book published in 1840, which I found nestled on the open stacks of The Providence Athenaeum — Thomas Dick’s The Sidereal Heavens, and other Subjects Connected with Astronomy, as Illustrative of the Character of the Deity, and of an Infinity of Worlds. This volume was indicative of the attempt to make observed science fit the Scriptures. Poe’s version turns the churchgoers’ cosmos inside out, but is ultimately just as ridiculous as its inspiration. (Click over the title to read or download Dick's book from Google Books. Click HERE to view a PDF of the title-page only.)

In January 1848, Mrs. Lynch invited Sarah Helen to contribute poetic greetings to a Valentine’s Day party she was planning for the New York literati. Helen and her sister Susan both sent poems. Helen’s was addressed to Poe.

Only after the February 14 party was over did Sarah Helen learn that Poe had not been invited, and was now in fact persona non grata among much of the literary set (certain people would not attend if they knew Poe was invited, etc. etc.). Anne Lynch then submitted 42 poems that had been read at her party for publication in the Home Journal. Helen’s poem was not among them.

It took two more communications to a reluctant Anne Lynch to get her to pass along the Poe valentine for publication. The Home Journal published it separately. Although the poem as originally written is a clear “come hither,” common friends assured Poe that Helen was dour and eccentric. None of these friends mentioned to Poe, perhaps intentionally, that Helen was a widow.

Sarah Helen revised her valentine poem substantially in later years, making its imagery encompass more of Poe’s writing. Since it is the poem that launched the love affair, I have included both versions in this edition. The original valentine is titled “To. E.A. Poe,” and the revised poem is titled “The Raven.”

Poe’s most recent biographer, Kenneth Silverman, in his book Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance, is the first to acknowledge that Helen was a formidable match for Poe intellectually. Unlike the dilettante ladies Poe knew in New York, Silverman observes, “Sarah Helen Whitman was a woman with sophisticated philosophical and literary interests — after her friend Margaret Fuller, perhaps the leading female literary critic in America.” He lists the depth of her literary studies, her love of Goethe, Shelley, Shakespeare and the Transcendentalists. He adds, intriguingly, “She also studied mesmerism and magnetic science, of which Providence was a center. Convinced that an Other World existed, she went beyond both Emerson and Mesmer in the pursuit of occult knowledge.”

At the time I assembled the first edition of this book, there were no Poe biographers making such generous assertions about Sarah Helen’s worth.

Only after interrogating one or more other literary women by letter did Poe learn that “Mrs.” Whitman was a widow. Fanny Osgood wrote to Helen, warning her with some humor that the New York raven would certainly descend on the Providence dove.

POE, who was beginning to thrash about for female companionship to center his life, was already commencing a long distance relationship with the first of two women in Lowell, Massachusetts.

The first was Jane Locke, who lured Poe to the mill city for a paid lecture and reading. In correspondence, Jane Locke sounded like a potential soul-mate, but her fevered letters were worded so cautiously that Poe could not ascertain her age, or even whether she was single, married, or a widow.

While still trying to figure out Jane Locke’s status, Poe responded to Sarah Helen’s “come hither” poem by tearing a page from one of his printed books — his early poem “To Helen” which was inspired by Helen Stanard, a married lady Poe was obsessed with in his youth. He sent the poem anonymously on March 2.

Then, in May, with the Muse on his side, Poe penned the longer prose-poem “To Helen,” which recollected the vision of Sarah Helen seen in her rose garden that summer night three years earlier. He mailed it anonymously to Helen on June 1. She matched its handwriting to the address of the envelope containing the earlier poem. A friend confirmed for her that it was indeed Poe’s handwriting.

As summer commenced, Poe was getting desperate to sort the ladies out. He was preparing his lecture for the mysterious Jane Locke in Lowell. At least he could investigate Sarah Helen long-distance. He wrote poet Anna Blackwell, who had recently been in Providence for “magnetic therapy,” asking “Can you not tell me something about her — anything — every thing you know — and let no one know that I have asked you to do so?”

In Lowell, Massachusetts, Poe gave his scheduled performance on July 10 — his new talk, “The Poets and Poetry of America.” He included special praise for the poetry of Mrs. Whitman. He tried not to appear quite so shocked as he was, when he discovered that his professed “soul mate,” Jane Locke, was a 43-year-old married women with five children. Mrs. Locke, after showing off the visiting poet to the other mill owners’ wives, would later give birth to an ecstatic long poem deifying Poe — the only fruit of her intended union with the famous writer.

During the Lowell visit, though, lightning struck. As he was dragged around to the Lockes’ relatives, Poe met the “other” woman: 28-year-old Nancy “Annie” Richmond. Poe fled the threatened embraces of Mrs. Locke, and stayed over at the Richmonds’ home at Westford. That night, he fell hopelessly in love (Platonic, brotherly love, of course) with “Annie,” who instantly became his sister, twin, goddess — almost enough to push the lamented Virginia out of the cosmos. One could almost hear Virginia’s ghost, coughing tubercularly, outside the Richmonds’ parlor.

“Annie” was conveniently married to an indulgent paper mill owner who didn’t seem to mind his wife entertaining and corresponding with a harmless, broken-down poet. Annie’s three-year-old daughter, far from daunting to Poe, seemed an angel next to the pawing horde of little Lockes.

Since the Richmonds were related to the Lockes, one can only imagine the repercussions of this poetic abduction, especially after Poe began inundating Annie with letters.

Back in New York, Poe’s book Eureka was issued by Putnam’s. Poe had tried to convince the skeptical publisher that this landmark book would be so popular that presses would run day and night to keep it in stock. It was then, and may now still be, the least-read book by any major American writer.

In late July, Poe was off to Richmond to try to raise funds for his long-dreamt-of magazine, The Stylus. There, he distinguished himself with a two-week drinking binge, incoherent visits to editors, a thwarted duel, and a reacquaintance with a lady named Elmira Royster. She is outside the ken of our story here, except that Poe almost proposed to her. It seemed a fatality of Poe’s that the further South he went, the closer to doom he came.

While he was in Virginia, two stanzas of poetry by Sarah Helen Whitman arrived. The lines were encouraging — she had read — she had understood. He may have sensed that the sterner, more sober lifestyle of New England was what he really needed. Perhaps Sarah Helen would be his salvation — if not, the divine Annie was near. Poe hurtled back northward.

ON Thursday, September 21, 1848 — an equinoctial, portentous date — Edgar Poe arrived in Providence, after devising a letter of introduction so that he could present himself to Mrs. Whitman in person.

On Friday, September 22, Poe and Helen toured a cemetery — purportedly Swan Point Cemetery. Some have questioned whether Poe and Helen ventured all the way to the then-rural Swan Point, more than three miles’ walk through dirt lanes and woods. Originally I was inclined to doubt this, too. The Episcopal Churchyard of St. John’s, just yards from Sarah Helen’s door, was one candidate, but prying eyes were everywhere there. The North Burial Ground, Providence’s traditional cemetery, was closer, and would have given her a chance to show Poe her relatives’ graves, as well as the stones of some of Providence’s founding fathers. But Swan Point, which had opened just two years earlier, was American’s second “garden cemetery,” and everyone was curious to see the new idea in landscaped, park-like cemeteries, even if the spot was not yet full of the neglected graves and crumbling old mausoleums that Helen’s recollections seem to suggest.

It is my opinion that they may have gone to the North Burial Ground, and that Helen romanticized the story by saying, years later, that they had gone to Swan Point. We do know, though, that Poe was avid about long walks, and Helen would have been grateful for the chance to talk about poetry and friendship away from the eyes and ears of mother and sister. If so, she must have come home late, exhausted, speechless, her shawls and scarves full of burrs, to the alarm of Mrs. Power.

If she smiled a quiet smile and refused to say much, it was understandable. In a secluded spot in the cemetery, Poe had put his arm around her waist and proposed marriage.

Poe stayed on until Sunday, September 24th. Presumably, in those days, he met some of Helen’s other friends, including the poetic Mr. Pabodie. Poe and Pabodie had much in common — both were poets with a leaning toward the hyper-romantic, funereal and supernatural; both detested the Boston literati; and both had dreams of founding a national literary journal. Pabodie had much to gain if Poe and Helen, his friends, remained in Providence and launched The Stylus.

As Poe learned just how close Sarah Helen still was to the New England literary circle, he grew alarmed: her friends were emphatically not his. He also learned that Helen was known to the whole circle of New York literary women, and could expect to receive letters from the likes of Mrs. Ellet, his social nemesis in New York. He began earnestly to warn Helen that his very real detractors would do anything they could to thwart his — and their — mutual happiness. Even more so would the envious mediocrities oppose the union of two poetic geniuses.

Because of transportation difficulties, Poe remained in Providence yet another day. On Monday morning, September 25 he went alone to Swan Point Cemetery. His train for New York was not until 6:00 in the evening. If this is actually what he did with his day, the long walk, similar to those he enjoyed during his better New York period, would have given him ample time to reflect on his potential new life. What he made of Mrs. Power and the moody Susan Anna, and how he thought the Poe-Whitman household would take shape, were doubtless foremost in his mind. Could Helen be persuaded to leave Providence and move with him to New York, where they would found The Stylus and begin their joint triumph over the kingdom of letters? Or would he move to Rhode Island and clean the Augean stables of the Transcendentalists?

Back in New York City, on September 30, Poe received Helen’s letter declining his proposal. Family duties, age differences, her health and other unstated issues were insurmountable, she said. And indeed, she had begun to hear unsettling things about him…

October arrived, and on its first day Poe worked up a proper fury writing his first love letter to Helen. On October 18th, he wrote another one. They are his longest, most impassioned letters, and they have been reprinted numerous times in Poe biographies.

In late October (the dates here are not certain), Poe was back in Providence again, asking Helen to reconsider her refusal. This is likely the time they spent showing one another their poetry and best work, especially in the shadowed nooks of the Athenaeum, away from Mother’s rebuking glances. Now Poe worked his magic, trying to convince her she was not too old, nor too frail, to be the companion who would save his soul. And he appealed to her as an artist, challenging her to the level of ambition required to join the immortals.

Since it seemed in Edgar Poe’s character to do the worst thing always, he appeared at Helen’s house more than once in an obvious state of inebriation. Perhaps Mr. Pabodie also introduced Poe to the pubs in Providence’s notorious North End, where sailors brawled and where the police frequently raided “common brothels” and “brothels of the lowest sort.”

His counter-arguments made, Poe then secured Helen’s promise that she would write to him with her reply.

ANOTHER INTERVAL WITH THE RICHMONDS

THINGS in Lowell did not turn out as planned. Poe found his first pretext to leave Mrs. Locke’s home and become a guest of the Richmonds once again. The sympathetic Annie Richmond showered Poe with sympathetic and sisterly affection, and Poe doubtless shared with her all his doubts and worries about the proposal to Helen. She may have counseled him to persevere in the marriage, knowing how desperately he needed a center for his life. Poe walked to the post office daily, looking for Helen’s letter, and was miserable each day when it did not appear.

The planned Lowell lecture was cancelled because of the distractions leading up to the 1848 Presidential election (possibly the lecture hall became unavailable). Poe thus lost a desperately needed lecture fee.

One consolation was a three-day visit to Westford, where this time Annie Richmond’s parents hosted Poe and Annie, and Poe was induced to read for an appreciative local audience. On one of these days, Poe took a long, solitary walk in the hilly countryside.

Poe’s presence in the Richmond home finally provoked the festering jealousy of Mrs. Locke. Open hostilities broke out between the Lockes and the Richmonds. By this time, the indulgent Mr. Richmond was doubtless alerted that something was improper about Poe’s attentions to his wife.

Around November 2, Helen finally wrote a brief, vague letter, which Poe received in Lowell, neither confirming nor denying the idea of an engagement, and this letter agitated Poe even more. On Friday, November 3, he sent back a note indicating he would be in Providence on Saturday. He now stood to lose the links to both of his New England women, the poetic bride and the Platonic sister-spirit.

Annie continued to encourage him in the marriage to Mrs. Whitman. Poe, in great turmoil, agreed to renew his courtship in Providence, but got Annie to promise that she would come to him if he were near death.

ON Saturday, November 4th, Poe arrived in Providence. Helen waited at her home, and Poe never arrived. Instead he spent what he called “a long, long, hideous night of despair.” It is hard to credit his claim that he spent the night alone in his hotel room. If there was any time he needed a drink, it was now…

Sunday dawned, and Poe decided to return to the city of his birth, Boston. There, he would kill himself, and summon Annie to be at his side for his final moments. Here is how he related it to Annie in a letter written two weeks later:

I arose & endeavored to quiet my mind by a rapid walk in the cold, keen air — but all would not do — the demon tormented me still. Finally I procured two ounces of laudanum & without returning to my Hotel, took the cars back to Boston. When I arrived, I wrote you a letter, in which I opened my whole heart to you — to you — my Annie, whom I so madly, distractedly love — I told you how my struggles were more than I could bear — how my soul revolted from saying the words which were to be said [proposing marriage once again to Mrs. Whitman]— and that not even for your dear sake, could I bring myself to say them. I then reminded you of that holy promise, which was the last I exacted from you in parting — the promise that, under all circumstances, you would come to me on my bed of death — I implored you to come then — mentioning the place where I should be found in Boston — Having written this letter, I swallowed about half the laudanum & hurried to the Post Office — intending not to take the rest until I saw you — for, I did not doubt for one moment, that my own Annie would keep her sacred promise — But I had not calculated on the strength of the laudanum, for, before I reached the Post Office my reason was entirely gone, & the letter was never put in.

Monday, November 6th was a lost day. In Boston, a good Samaritan helped Poe, quite of his mind, find and board the train, not to Lowell, but back to Providence.

On Tuesday morning, November 7, Poe came to the Power house on Benefit Street early in the morning and demanded to see Helen. Helen sent word through a servant that she would see him at noon. Poe insisted to the servant that he had to see Helen at once, because he had an engagement later. Rebuffed, Poe went back to his hotel and scribbled a note that read:

I have no engagements, but am very ill — so much so that I must go home, if possible — but if you say ‘stay’, I will try & do so. If you cannot see me — write me one word to say that you do love me and that, under all circumstances, you will be mine. Remember that these coveted words you have never yet spoken… It was not in my power to be here on Saturday as I proposed…

Helen met Poe later that morning at the Athenaeum. Helen accepted Poe’s explanation that he had taken laudanum to “calm himself” and had suffered an overdose. He chided her for delaying her letter to Lowell for so long, and urged her to marry him immediately and return with him to New York.

The next day, Wednesday, November 8, the two poets had recovered their equilibrium. Now it was Helen’s turn to balk. She had received several letters from New York cautioning her about Poe and his drinking. Helen herself later wrote:

[H]e had vehemently urged me to an immediate marriage. As an additional reason for delaying a marriage which, under any circumstances, seemed to all my friends full of evil portents, I read to him some passages from a letter which I had recently received from one of his New York associates. He seemed deeply pained and wounded by the result of our interview, and left me abruptly saying that if we met again, it would be as strangers.

Helen assumed that Poe, who had written her a tortured farewell note from his hotel, had taken the evening train to New York. But Poe was going nowhere. He may not even have had the train fare. Instead he spent the evening in the bar-room of his hotel. We can imagine “The Raven” and “Eureka” intoned, others paying for the visiting celebrity’s drinks, and the refrain of “Nevermore!” shaking the rafters. We can imagine Poe in his cups, reading the one poem certain to make him think of Virginia … and what might he have said, in his bitterness, about the dainty widow on the hill? And Mr. Pabodie was always about, making us wonder, too, where Poe obtained his laudanum.

Helen passed a night of “unspeakable anxiety in thinking what might befall him traveling alone in such a state of mental perturbation and excitement.”

Sometime during the night, a man named MacFarlane attached himself to the miserable poet, and saw him through the night. In the morning, MacFarlane dragged him to Masury & Hartshorn’s daguerreotype parlor, where Poe permitted himself to be immortalized in his misery. This is the famous “Ultima Thule” portrait, showing Poe with his face distorted — the lingering after-effect of the drug overdose, combined with the emotional crises which had accumulated upon him.

It was the morning of Thursday, November 9. Helen wrote: “He came alone to my mother’s house in a state of wild and delirious excitement calling upon me to save him from some terrible impending doom. The tones of his voice were appalling and rang through the house. Never have I heard anything so awful, awful even to sublimity.” It would not be too far a stretch to guess that Poe had taken another laudanum “calmative,” for this behavior does not sound like a mere hangover.

Poe stayed in the house for several hours. When Helen finally had the nerve to enter the parlor, Poe hailed Helen as an angel and clung to her, tearing away a piece of muslin. A doctor was summoned, and brain congestion was the diagnosis. Mr. Pabodie was on hand, and as a devotee of the poppy, he might have known a lot more about Poe’s condition than the doctor. Poe was removed to Pabodie’s house, where he lodged for a few days.

By November 13, Sarah Helen felt that Poe was himself again. He seemed to have worked an almost mesmeric spell over her. They went together to the daguerreotype parlor and had Poe photographed. At this point, to everyone’s astonishment, Helen agreed to a conditional engagement, provided that Poe pledged to absolutely refrain from drinking. If Poe behaved as a model suitor, she hoped to persuade her mother to approve the marriage, perhaps as soon as December.

Satisfied, Poe left on the six o’clock train for Stonington, from where he would get the steamer boat to New York.

Within hours, Helen and her mother heard some gossip about Poe’s recent conduct — possibly an account of how much and how often he had imbibed while in Providence, and only blocks from the Benefit Street home. These new reports “augmented almost to phrenzy” Mrs. Power’s opposition to the union. Helen’s response was to scan the heavens and write the first of her poems “To Arcturus.”

ENGAGED, BUT FULL OF FOREBODING

On November 14th, Poe was reinstalled at the cottage at Fordham. He and Helen exchanged more letters. Poe called Helen “beloved of my heart, of my imagination, of my intellect” but added ominously, “I am calm and tranquil and but for a strange shadow of coming evil which haunts me I should be happy. That I am not supremely happy, even when I feel your dear love at my heart terrifies me. What can this mean?”

By late November, other missives were flying. Mrs. Anne Lynch in New York wrote to William Pabodie to ask if the rumors of the Edgar Poe-Helen Whitman engagement were true. Fannie Osgood rushed to Providence and called on Sarah Helen. Unlike the others, she defended Poe. As Sarah Helen later recalled, “She threw herself at my feet & covered my hands with tears & kisses; she told me all the enthusiasm that she had felt for him & her unchanged and unchanging interest in him & his best welfare.”

Poe, for his part, spent November writing Helen several long letters detailing the vengeful nature of his enemies on the New York literary scene. He convinced Helen of their frenzied desire to do him harm.

Sometime after December 7, Poe had returned to Providence. On December 12th, Poe sat with Helen and read her long poem,“Hours of Life.” If he had any doubts about her poetic worth, or the quality of her mind, he now knew he had a formidable mate. He urged her to complete the poem and publish it as soon as possible. On one of these evenings, Poe and Helen sat silently on opposite sides of the Power parlor. Helen stood, as if under a hypnotic power, and walked to the center of the room, where Poe embraced her. They kissed, and then Helen went to sit at Poe’s side. All this without a word spoken.

Poe returned by train and steamer to Fordham. His mother-in-law, Mrs. Clemm, had to be prepared for the news, and it is likely that Poe did not have the money in pocket to remain day after day in a hotel, not to mention the daily expenses of the courtship.

Seeing that Helen was determined to marry Poe, the Power clan swung into action. On Friday, December 15, Mrs. Power, consulting with Charles F. Tillinghast, administrator of the Marsh estates, drew up an agreement in which Helen transferred all her money and property to her mother. This would prevent Poe from having any access to the family estate and funds. Sarah Helen dared not oppose her mother, and wrote to Poe and Mrs. Clemm with this unpleasant news.

Poe’s reply to Helen was reassuring. On Saturday, December 16 he wrote:

My own dearest Helen — Your letters — to my mother & myself — have just been received & I hasten to reply … I cannot be in Providence until Wednesday morning and, as I must try and get some sleep after I arrive, it is more than probable that I shall not see you until about 2, P.M. Keep up heart — for all will go well. My mother sends her dearest love and says she will return good for evil & treat you much better than your mother has treated me.

While visiting poet Mary E. Hewitt in New York City, Poe expressed a very different opinion about whether the intended marriage was going to happen. He told her, repeating his words twice for emphasis, “That marriage will never take place.”

On Wednesday, December 20, Poe arrived early in the morning and checked into the Earl House at 67 North Main Street. At 7:30, Poe delivered his Franklin Lyceum lecture at Howard’s Hall, to an audience of 1800 to 2000 persons. Sarah Helen sat in the front row. His lecture, “The Poetic Principle,” showed Poe at his best. He also read “The Raven” and the early version of “The Bells.”

That night, flush with success and with his speaker’s fee in pocket, Poe fell in with a group of dissolute young men at his hotel (so Pabodie described them, and we suspect he knew them). They persuaded the famous poet to drink with them. And with Poe, that meant drink after drink, and choruses of “Nevermore!”

On Friday, December 22, Poe arose in his hotel. He dressed and went out for breakfast, but the hotel bar was already open. So he went in and had a glass of wine. Who would know?

At Helen’s home a little later, Poe was required to sign the Power family property transfer agreement as a witness. It must have been a moment of supreme humiliation. Pabodie also signed the agreement as a witness. It was now plain that if he married Helen, she would go with him to Fordham as a penniless woman with a trunk full of clothes and books. If he broke off the engagement at this point, he would be branded forever as a fortune hunter and a man without honor.

The arrangements continued with grim determination. The pace suddenly accelerated: Mr. Pabodie was asked to contact the minister and make official arrangements for a Monday, December 25 wedding. The process of “publishing the banns” meant that the intended marriage was to be announced on Sunday in the church in the week preceding the marriage. In earlier times, the banns were announced three weeks in succession, during which period anyone in the congregation had a chance to raise objections, legal or moral.

Pabodie put the note from Poe to the minister in his pocket but did not deliver it to St. John’s church, which was a stone’s throw from Helen’s house. Was this at Poe’s request? Or was this done in connivance with Mrs. Power? Or were they all, Helen included, going through motions they wished some Providential force would interrupt?

Poe seemed to treat the marriage as a certainty. He sent off a note to Mrs. Clemm that read “We shall be married on Monday [Christmas Day], and will be at Fordham on Tuesday, in the first train.” If a Christmas Day wedding sounds unlikely to modern readers, I am assured from a perusal of Stephen Nissembaum’s The Battle for Christmas that New England was decades away from marking Christmas as a cardinal church or state holiday. A Christmas Day wedding was not, therefore, objectionable or unusual, but it was certainly sudden.

Oppressed by the atmosphere of the Power house, Poe and Helen fled to the quietude of The Athenaeum. There, nestled amid the dimly-lit stacks, the two poets sat together. Both of them were beleaguered by events, and human nature being what it is, they may have been even more resolved to make the whole thing work. Life in New York would be difficult, but Poe was famous, a sworn reformed man, and they both had many friends there.

This was the moment, as in every Greek drama, when a messenger arrives with disastrous news. A messenger boy ran into the Athenaeum, breathless, asking for Mrs. Whitman. He handed her a letter. It was urgent, he said, that she read it at once. She opened the envelope and read in silence.

I will let Helen tell the rest of what transpired a little later back at the Power house:

Recollect — we were to be married in a few days. Poe had at last prevailed upon me to consent to an immediate union. He had written to Dr. Crocker to publish the “banns of marriage” between us. He had written to Mrs. Clemm to announce our arrival in New York early in the following week, when it came to my knowledge & the knowledge of my friends, that he had already broken the solemn pledge so lately given by taking wine or something stronger than wine at the bar of his hotel. No token of this infringement of his promise was visible in his appearance or his manner, but I was at last convinced that it would be in vain longer to hope against hope. I knew that he had irrevocably lost the power of self-recovery.

Gathering together some papers which he had entrusted to my keeping, I placed them in his hands without a word of explanation or reproach, and, utterly worn out & exhausted by the mental conflicts & anxieties of the last few days, I drenched my handkerchief in ether & threw myself on a sofa, hoping to lose myself in utter unconsciousness. Sinking on his knees beside me, he entreated me to speak to him-one word, but one word. At last I responded almost inaudibly, “What can I say?” “Say that you love me, Helen.” “I love you.”

Those three words were the last I ever spoke to him. He remonstrated & explained & expostulated. But I had sunk from a violent ague fit into a cold and death-like stupor. He brought shawls and covered me with them, & then lifting me in his arms, bore me to a lounge near the fire, where he remained on his knees beside me, chafing my hands & invoking me, by all tenderest names & epithets, to speak to him again, one word. A merciful apathy was now stealing over my senses, & though I vaguely heard all, or much, that was said, I spoke no word, nor gave any sign of life. My mother & sister & another friend were in the room. I heard my mother remonstrating with him & urging his departure.

Then Mr. Pabodie entered the room and joined my mother in entreaties that he would leave me. Her last words I did not hear, but I heard him haughtily and angrily reply, “Mr. Pabodie, you hear how I am insulted.” These were his last words, & the door closed behind him forever. His letters I did not dare to answer. Exaggerated and humiliating stories were in circulation. He entreated me to deny them, to say that I at least had not authorized them. I never answered the letter.

Within days, everyone knew, from Providence to New York, how Poe had courted and lost the poetic Mrs. Whitman. Each telling of the scene in the parlor became more melodramatic, until it finally seemed that the militia had been called to remove the deranged poet from the premises. Meanwhile, to the mortification of all parties, newspapers all over the Northeast noted the impending nuptials, one of them even looking forward to a clan of little Poes.

What was really in the letter that made Helen break off the engagement? Helen discreetly said it was about Poe’s glass of wine in his hotel that morning, but it was probably a litany of all of Poe’s recent transgressions, gathered by a loose conspiracy of vagrants, snitches, Temperance bar-watchers, and maybe even an off-duty police officer or two. An artist could have dashed off sketches from the Poe daguerreotype, facilitating a near-total “Poe watch” in the neighborhood. Any words that Poe uttered in his drinking escapades might also have been repeated. (Almost all of Poe’s biographers have marveled at the flow of gossip in Providence, so I’m making the leap to guess that Helen was given an unvarnished precis of Poe’s activities.)

Thus it is hard to avoid feeling that Poe was being watched, probably from the time he was photographed on November 9. Poe also had the distinct feeling that he was being followed and watched all the way back to New York.

Some Poe biographers have assumed that the fatal missive contained details about Poe’s squabbles with the lady poets in New York, but he had already told her about that. Others suggest she received a letter about Annie Richmond — but Helen did not know about the simultaneous letters to Annie until almost thirty years later. More likely, the letter was all the local gossip someone had gathered on Mrs. Powers’ behalf, if not at her behest.

Helen remained silent about the whole affair. Later, she published a poem to tell Poe indirectly of her undying affection for him. Poe, for his part, may have written “Annabel Lee” to memorialize their romance. But before they could ever meet again, Poe was found in a stupor on a Baltimore street during the crazed days of a local election. He died, drifting between lucidity and delirium, on October 7, 1849.

Sarah Helen Whitman lived for three more decades. In 1853, she published the poems she had written to and about Poe. In 1860, two years after the death of her mother, she published Edgar Poe and His Critics, a small but well-reasoned defense of Poe’s writing and reputation. Although she seldom left Providence, she published her poems in major magazines and newspapers, and maintained correspondence with writers around the world. Her loyalty to Poe and her unselfish help to Poe biographers over the decades helped turn the tide of popular opinion against those who had depicted him as an amoral villain. Helen’s achievement is one of the great vindications in literary history.

In the years until 1860, Helen was generally silent about her relationship with Poe. She relied upon friends to defend her honor — and Poe’s. After the infamous “memoir” of Poe published by Rufus Griswold circulated wild and exaggerated stories about Poe and his conduct, William Pabodie published a letter in The New York Tribune in 1852, refuting some of Griswold’s slanderous and distorted history. When Griswold threatened Pabodie with a libel suit in return, Pabodie defied him and published another letter showing further falsehoods in Griswold’s writing. (It is a touching irony that Griswold’s later life would be ruined by Mrs. Ellet, who had been Poe’s nemesis among the literary women of New York.)

Helen Whitman remained in touch with Mrs. Clemm, Poe’s mother-in-law, and sent her many gifts of money over the years. She became a devoted correspondent to Poe’s admirers and biographers, both in America and overseas.

After Mrs. Power’s death in 1858, Helen and her sister purchased another house, which was moved in the 20th century from its original location to 140 Power Street. The home was Sarah Helen’s literary salon, seance parlor and sanitarium for her sister. Susan Anna Power, who seems to have drifted into religious mania, lived until December 8, 1877. Sarah Helen Whitman fell ill shortly after her sister’s death, and was moved to the home of friends on Bowen Street, where she died June 27, 1878.

Helen continued all her life to defend Poe’s honor and reputation. She did not learn the details of Poe’s letters to Annie Richmond, and how exactly contemporaneous they were with her courtship to Poe, until her last year, when John Henry Ingram published a group of Poe’s “Annie” letters. It was a bitter discovery.

Biographies of Poe make him either saint or monster. The monstrous image got its impetus from the exaggerations if not calumnies of the Reverend Rufus Griswold, who libeled Poe after his death, even while acting as his literary executor. Other literati whom Poe had criticized and mocked in his reviews joined forces with the society of spurned “literary ladies” to cement the present-day image of Poe as a drunkard, perennial drug addict, and less-than-honorable pursuer of the female sex.

Overzealous admirers, on the other hand, would have us believe that Poe never took a drink, told a lie, or felt a dishonorable affection. The need to “whitewash” literary figures may be hard for today’s readers to understand. We are not that far away from a time when the right sort of people did not read books written by the wrong sort of author. The works of Poe, Shelley, Lord Byron and Walt Whitman were all banned from homes and libraries as much for the behavior or demeanor of the authors as for the content of the works.

The fight for Poe’s reputation, therefore, began with a kindly motive: to fight for his place in the history of our literature. But the time for sanitizing is long since over — today we want the whole man, blemishes and all. With Poe this is a challenge because the worst has already been said about him, and we must sort out what to believe and what to discard. The Poe-Helen narrative is especially troublesome since we are forced here to examine Edgar Allan Poe during a period of troubled decline.

An artist of Poe’s intellect, passion and imagination was by necessity an outsider to convention. In Poe we see a man of brilliance and integrity who was nonetheless driven by his passions to dangerous contradictions.

His flirtations with the literary women of his day are perfect examples of his contradictory nature. There is nothing more typical of the poetic impulse than to fall into an abstract, other-worldly infatuation with someone unattainable. Poe attracted the attentions of a number of women poets. In the hothouse society they frequented, they all met and competed for the attention of the real poetic lions. They wrote valentines and structured acrostic verses around their names and initials. They encouraged passionate, personal letters.

This might seem to the jaded modernist a mere prelude to adultery. In Poe’s case these poetic flatteries were likely the only “embraces” actually exchanged. Some of Poe’s friendships with his lady poets were conducted in the full presence and acquiescence of amused husbands and other family members. To Poe, the lady poets were sensitive and clever, but hardly serious. Their poems and letters to him were praise; his to them, flattery and gallantry. In both types of exchanges, hyperbole was expected.

This is not to say that Poe’s affections for various women, including Sarah Helen Whitman, were unreal. Poe seems even to have understood how this aloof literary and intellectual passion would be his battery. An early poem, “Romance,” rather clearly spells out his feeling of being foredoomed to impossible, but fructifying, infatuations:

I could not love except where Death

Was mingling his with Beauty’s breath —

Or Hymen, Time and Destiny

Were stalking between her and me.

These couplets could very well be the motto of Poe’s entire romantic life: his attraction to women doomed to die of consumption; for safely married women; for women too old to properly return his passion (the first Helen of his boyhood, and, perhaps, even the wife of his adoptive guardian, Mr. Allan); and for Sarah Helen Whitman.

In his story, “The Imp of the Perverse,” Poe also defined the impulse which drove him to his quixotic passions — yea, to do the very thing that he knew would be the worst possible course of action in a given situation. He wrote:

a paradoxical something, which we may call perverseness, ... through its promptings we act without comprehensible object … we act for the reason that we should not … the assurance of the wrong or error of any action is often the one unconquerable force which impels us, and alone impels us, to its prosecution … It is a radical, a primitive impulse — elementary … The impulse increases to a wish, the wish to a desire, the desire to an uncontrollable longing, and the longing … is indulged … There is no passion in nature so demoniacally impatient, as that of him, who shuddering upon the edge of a precipice, thus meditates a plunge...I am one of the many uncounted victims of the Imp of the Perverse.

I arranged the poems in this book to recreate the courtship, parting and remembrance of Helen and Poe. In the first section of the book, Poe’s masterpiece “The Raven” is answered by Helen’s valentine of the same title. Then each poet introduces characteristic poems, emphasizing their respective solitude.

Then, they demonstrate some of their best work to one another — both in love poems and in their verses on more far-ranging subjects. I chose poems they might have read to one another, pieces that would serve to deepen their mutual admiration.

Next come the poems associated with their parting, and the two poems that might have led to reconciliation — Helen’s “Our Island of Dreams” and Poe’s “Annabel Lee.”

The remaining poems are Helen’s posthumous tributes to Poe, and several additional Poe poems chosen for counterpoint. I believe this “dialogue” of poems shows both writers to their best advantage.

Among the fine later poems, Sarah Helen Whitman’s “Proserpine, To Pluto, In Hades” deserves special attention for its personification of the characters in our drama. The poet uses the familiar mythical story of Ceres’ daughter, Proserpine (Persephone in Greek), who must spend six months of the year with her brooding husband, Pluto, lord of the dead, and six months of the year above ground. This ancient fable explaining and symbolizing the seasons is turned topsy-turvy by Helen. Her Proserpine loves Pluto and prefers to sit by his throne in the dark underworld. Her angry mother Ceres comes in a chariot drawn by two dragons to reclaim her. Here we have, a trio of archetypes: Helen, Poe and Helen’s ever-angry mother. The Persephone symbolism even carried to Helen’s funeral in 1878: her coffin was decorated with a green wreath, and a stalk of wheat.

HELEN Whitman’s longest and most ambitious poem is “Hours of Life.” The middle section of that poem, “Noon,” is included in this revised edition. It was excluded for reasons of space from the first printed edition. “Noon” is a spiritual saga and romantic quest — the poet’s search for meaning and truth through the realms of myth and antiquity. In this long poetic odyssey we see: Echoes of Goethe in a passage that is almost a paraphrase of the famous scene of Faust alone in his laboratory, before he makes the acquaintance of Mephistopheles … A fascinatingly brief flirtation with the vengeful god of the Old Testament, whom she rejects … A wise examination and rejection of the sad religion of the Hindu … as well as the death-obsessed Egyptian … A passionate, almost Shelleyan plunge into the world of Ancient Greece, where she obviously feels close to the very origins of myth and meaning. Her use of the Dionysian Maenads — fierce, wild, drunken women, running down the mountain slope toward her as in a nightmare, crying out “Evoe — ah — Evoe!” is the most elemental, and frankly terrifying thing in all her writing. In fact, it is more Chthonic and real than many of the terrors in Poe’s poetry.

She wrests herself away from the refrain of the Maenads only by turning to Nature. Here she waxes almost Byronic in taking comfort from the rude, natural world. She finds that she can accept this transcendental, all-encompassing Nature, free of the eidolons of ancient gods.

One thing only troubles her, though — the doubt that would bring her back to a more conventional, if still highly individual, resolution, in the third part of the poem. What about the abyss after death? she asks. Nature is not enough if the spirit does not survive and transcend the body. Thus she leaves her quest, Faust-like, with no satisfaction from all she has seen on her journey.

The beauty and power of “Noon” is easily obscured by the more conventional opening, and the rather spiritualist closing of the longer poem of which it is part. But “Noon” itself is a remarkable production, a piece Romantic in the purest sense. The very idea of a Providence widow in her darkened rooms on Benefit Street writing such an impassioned, fully-worked out quest in verse is amazing. This poem has nothing much to do with Poe — but everything to do with why Poe must have been drawn to her.

I CONSIDERED including the letters of Poe to Helen in this volume, but decided not to for several reasons. First, the letters have been reprinted and excerpted many times, and are readily available to readers. Second, while the poems seem to form a cohesive unity of encounter and reminiscence, and are markedly similar in style, no such colloquy could be created with Poe’s and Mrs. Whitman’s letters.

Poe’s letters to Helen are direct, passionate, immediate.

Helen’s letters to Poe have not survived. Instead, we have from her hand the cautious letters, written in latter years, to Poe’s admirers and biographers.